Mycology is a branch of science best known for the study of fungi, but it also includes the study of slime moulds — a group of little-known organisms that, although separate from fungi, are often studied together. Both groups contain a huge variety of forms, colours and sizes, but more often than not, slime moulds go unnoticed.

Last summer was hot and dry, but luckily, what followed was a period of rain, perfect weather for fungi to sprout.

This was very apparent when I went to Strumpshaw Fen in the early morning on the 12th August — there was an astonishing variety of fungal life: variously-coloured troops of Laccaria bicolour (Bicoloured Deceiver) and small scattered groups of Amanita phalloides (the Death Cap).

But even more interesting was the variety of slime moulds: bright yellow Fuligo septica, coral-pink Tubifera ferruginosa, silvery grey Arcyria cinerea and snowflake-like Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa all appeared on the rotting logs throughout the reserve woodland.

These are some of the more obvious species, but many are small and hard to spot — for example species of Stemonitis (“stemon” meaning “thread” and “itis” meaning “named after”).

If slime moulds are not part of the fungal Kingdom, where do they belong?

Slime moulds are a group of organisms in the Kingdom Protista (Protozoa) comprised of three classes: the Myxomycetes (true slime moulds), dictyostelids and protostelids. It is usually only the Myxomycetes that are visible and recorded with the naked eye.

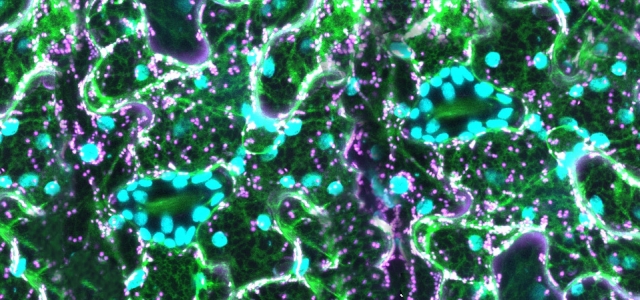

Myxomycetes exist primarily as single-cells, but, when conditions are right, they group together to form what is essentially one organism — a moving, feeding, multinucleate plasmodium [1].

These plasmodia are typically vein-like in structure, and move by “ebbing and flowing”, much like a sea wave. They feed by phagocytosis — engulfing their prey — which can be anything from leaf litter to plastics and pollutants.

Above is a spectacular specimen of Stemonitis flavogenita (“flavo-” meaning yellowish) found in Spring 2023. At the top left, it is in its plasmodial form, enabling it to move about — but this one seems to be forming distinct groups.

This is all part of the slime mould life cycle — once they’ve found the right spot, they will begin to form multicellular ‘clumps’, around which the organism centres and grows into a fruiting body. Of these there are four different types: sporangia, plasmodiocarp, aethalia and pseudoaethalia. As S. flavogenita shifts into a fruiting body, it produces long, thin sporangia which fade and become a dull brown, as in the top right and bottom left photos.

Species of Stemonitis earn the nickname ‘pipecleaner slimes’ because of the shape of their sporangia. The orangish, wet droplets are the moisture exuded as it begins to dry out [5].

After this stage, each ‘pipecleaner’ turns into a mass of rust-coloured spores, as shown in the bottom right photo.

Below is Tubifera ferruginosa (Ferrug– means “rusty” or “rust” and -osa means ‘fullness’ or ‘abundance’ [4]) a coral-pink slime mould in an immature pseudoaethalium form. When mature, these ‘clumps’ will turn into dark brown or black masses.

In some slime mould species, like this one, sporocarps begin as sporangia, then fuse into an aethalium-like structure. However, these retain the side walls between separate sporangia — in the image above you can see the individuals [2].

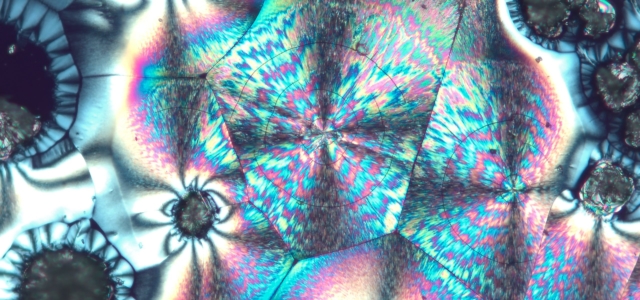

Below is Fuligo septica, one of the most recorded slime moulds, in its easily-identified aethalium form. The yellow part is a layer called the cortex which protects the spores underneath; the white substance at the edges is the hypothallus, attaching the fruiting body to the substrate [2].

This specimen appeared in Felbrigg woodlands in late Summer.

You can cultivate slime moulds at home. In general, the process is simple: collect some decaying woodland matter in a plastic tub, then bring it home and keep it in damp, room-temperature conditions and see what grows [6]. But I find it easier to just go for a walk in a woodland area and see what I find.

In Autumn 2022, I completed a mycological survey of the wooded area of Strumpshaw Fen. So when I signed up for the Silver Youth STEMM Award this summer, I decided another survey would be perfect as a research project: this time not only to improve my identification and recording skills, but also to see how and when different species appear throughout autumn.

What I didn’t expect was the bloom of slime moulds — particularly Fuligo septica — in early Autumn, when they grew all over the woodland.

I had thought that slime moulds, like fungi, grew best in colder, damper environments. But after some internet searching, it became clear that the ideal conditions for slime moulds actually include diurnal temperatures of 20 – 38 degrees celsius [2] — much higher than the typical mid and late Autumn temperatures in Britain.

One might assume that slime moulds are more prolific in tropical areas, but they are actually more often recorded in temperate regions. It is believed that this is because heavy rain can wash away the visible forms; others hypothesise that the myxomycetes which grow in the tropics only occasionally form fruiting bodies, so are recorded less often [1].

They can actually be found almost all year round. Next time you go for a walk in the woods, see if you can spot any!

If you are interested in seeing more of Arwen’s findings from Strumpshaw Fen through Autumn and Spring, check out her website: www.amcalenan.uk

References:

[1] Bustmold Website https://library.bustmold.com/myxomycetes/

[2] Myxomycetes: Biology, Systematics, Biogeography and Ecology, edited by Carlos Rojas and Steven L. Stephenson

[3] 2.4.2.1: Slime Moulds https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Botany/Botany_(Ha_Morrow_and_Algiers)/02%3A_Biodiversity_(Organismal_Groups)/2.04%3A_Protists/2.4.02%3A_Heterotrophic_Protists/2.4.2.01%3A_Slime_Molds

[4] Tubifera ferruginosa https://www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/club%20and%20coral/species%20pages/Tubifera%20ferruginosa.htm

[5] Stemonitis flavogenita http://www.bucksfungusgroup.org.uk/articles.html

[6] https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/lifesci/outreach/slimemold/wildslime/