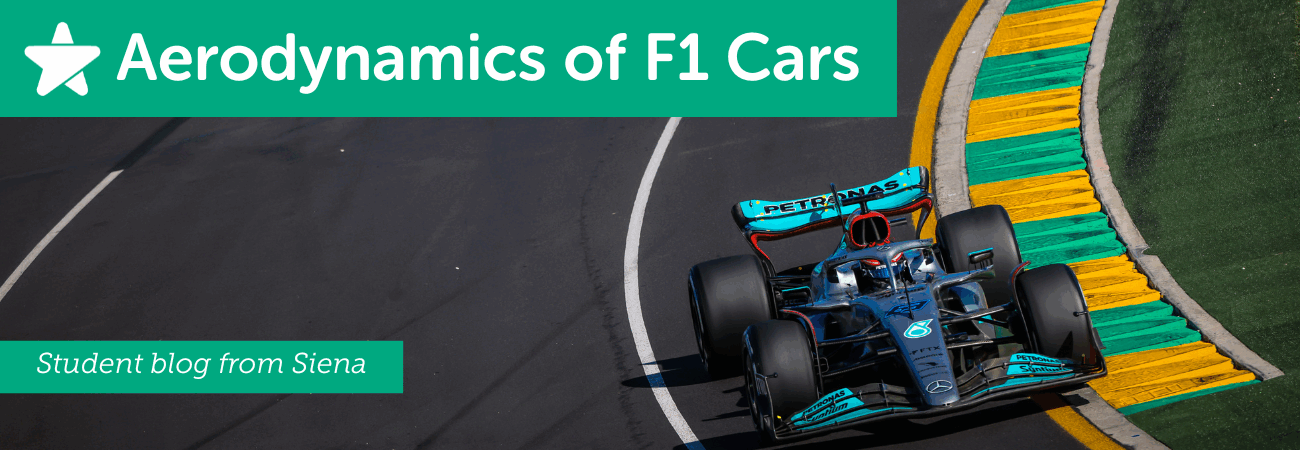

Reaching over 200 miles per hour, Formula 1 cars are some of the fastest machines in the world, and their design is all about speed and control. In her post, Siena explores how physics helps engineers push racing technology to its limits.

What is meant by aerodynamics?

Aerodynamics is the study of the properties of moving air and the interaction between air and solid objects moving through it [1]. Anything that moves through air is affected by aerodynamics. It explains the forces air can put on an object as it moves.

Why are the aerodynamics of an Formula 1 (F1) car important?

The overall design of an F1 car is greatly influenced by aerodynamics. They are designed to reduce drag and increase downforce (how much you want depends on the track and weather conditions). Generating downforce pushes the car down onto the track, generating more grip in the tyres. This means the cars can go faster around corners and accelerate faster on straights [2].

How can you visualise the aerodynamics on a F1 car?

To study the aerodynamics, F1 teams use a variety of techniques:

- Flow visualisation paint (flow-vis): It is a mixture of fluorescent powder and a light oil, applied in copious quantities on the car before it goes onto a track. While the car is moving through air on track, the paint will dry as the oil evaporates so you can clearly visualise the flow of air around the bodywork [3].

- Wind tunnels: These can be built in different sizes for full-size models or scaled down ones. They can create a controlled flow of air around the car. By using smoke, engineers can observe the air flow patterns created by the car. Sensors can be placed across the stationary car to measure forces.

- Computational fluid dynamics (CFD): This software can simulate airflow, streamlines and pressure distributions.

Using CFD compared to a wind tunnel [4]

CFD is much more cost effective than constructing a wind tunnel and does not require extra materials for each individual car variation. The flexibility and modification options of CFD greatly overshadow a wind tunnel as it is very easy to adjust the wind velocity, density and temperature in a short timeframe. The physical modifications required for a wind tunnel are much more time-consuming when also considering that CFD can run multiple simulations rapidly. While the accuracy of a wind tunnel is higher, it has some physical limitations such as high velocities which may be difficult to replicate. CFD is not restricted by any physical boundaries and offers additional detail. Despite CFD’s clear advantages, CFD still needs wind tunnel validation and is essential for studying scenarios which could be difficult to simulate. The most effective results come from integrating the two techniques, capitalising on their respective strengths.

Design aspects of the car which are influenced by aerodynamics

Front and rear wing:

The front wing is responsible for guiding air around the rest of the car as it is the first part of the car that encounters undisturbed air. It prepares the air flow, so it hits the car in the correct way to optimise the other aspects of the car. Made up of many components, it is often developed throughout the course of the F1 season however, the regulations for a front wing are very strict, creating very little freedom and variation from other cars in the paddock [5].

Meanwhile, the rear wing creates a significant portion of the car’s downforce (about a third of downforce is due to the rear wing). Downforce is produced because the air moves faster over the top of the wing, creating a low-pressure area, while the slower-moving air underneath creates higher pressure. This pressure difference pushes the wing – and the car – downward. Also, due to Newton’s third law, the wing’s upward deflection of air results in an equal and opposite reaction on the wing [6]. Because of its design, the rear wing generates drag, slowing the car. The greater the downforce it produces, the more drag. As a result, the F1 team must find a balance between the two. A factor which influences that crucial decision is that the rear wing incorporates a feature known as DRS (drag reduction system). This system uses a flap which can be opened to reduce aerodynamic drag. On straights, drivers activate DRS to minimise the drag caused by the rear wing, sacrificing some downforce to reach higher speeds by 10-12 kph [7].

Wing end plates located at the end of the front and rear wing direct streamlined and efficient airflow around the wings and reduces turbulence.

Side pods:

Side pods are a highly innovative section of the car and vary a lot between cars on the grid. They have two main functions: cooling internal components and controlling airflow. The airflow through the sidepods is utilized to cool the engine, gearbox and hybrid system components [8]. The airflow control is used to generate downforce as well as channel air into other aerodynamic components of the car such as the floor or influence the wake of air leaving the car.

Ground effect:

This effect generates significant downforce by creating a low-pressure area under the car to suction it to the track. This is done by accelerating air through tunnels on the car’s underfloor. The tunnels accelerate air by constricting the airflow, a wide inlet then narrows forcing the air through [9].

Porpoising:

The term porpoising comes from the animal porpoise, it is known to bob up and down which is effectively what happens to the car. It is an aerodynamic phenomenon that began to happen after the reintroduction of the ground effect in 2022. The faster the car goes, the more the ground effect pulls the car towards the ground. If the car gets too close to the ground, the airflow can stall, and the downforce generated disappears, so the car bounces back up again. The air flow can then go back under the car and repeats this cycle; the car aggressively bobs up and down. The driver can easily feel this effect which can be very uncomfortable and dangerous for the driver’s health. To try preventing this, cars have been raised higher above the ground, compromising performance, as it sacrifices downforce and speed. The FIA had to intervene and create a minimum height for the cars as no team wanted to sacrifice the speed gained by the car being closer to the ground [10].

References:

[1] bab.la, aerodynamics, year not listed. Available at: https://en.bab.la/dictionary/english/aerodynamics

[2] RacingNews365, Aerodynamics in F1, 2025. Available at: https://racingnews365.com/aerodynamics-f1

[3] Formula1, Testing explained: Rob Smedley on flow-vis paint, 2025. Available at: https://www.formula1.com/en/latest/article/testing-explained-rob-smedley-on-flow-vis.7nU2VePGlVrhIGa8wgCoLE

[4] Irena Kirova, CFD or Wind Tunnel? 6 Most Important Benefits of Digital Flow Simulation for Engineers, 2024, Dlubal. Available at: https://www.dlubal.com/en/support-and-learning/support/knowledge-base/001912#:~:text=CFD%20enables%20rapid%20design%2C%20iteration,as%20free%20from%20physical%20limitations.

[5] Rosario Giuliana, Tech 101: How does a Formula 1 front wing work?, 2020, Motorsport Week. Available at: https://www.motorsportweek.com/2020/08/24/tech-101-how-does-a-formula-1-front-wing-work/

[6] Matt Gellert, Formula One downforce: how air makes cars stick to the track, 2024, TechSight. Available at: https://techsight.co/index.php/2024/09/15/formula-one-downforce-how-air-makes-cars-stick-to-the-track/

[7] Motorsport Tickets, What is DRS in F1?, 2025. Available at: https://motorsporttickets.com/blog/what-is-drs-f1/

[8] Franky_TZ, Aerodynamic Components on F1 Car, 2012, Franky F1 Aerodynamics. Available at: https://tianyizf1.wordpress.com/2012/08/28/aero-components-f1-car/

[9] Scott Mansell, Aerodynamic Floors and Diffusers in F1 – How do they work?, 2024, Fluid Jobs. Available at: https://fluidjobs.com/blog/aerodynamic-floors-and-diffusers-in-f1-how-do-they-work-

[10] Jack Holding, What is porpoising? F1’s aerodynamic phenomenon explained, 2023, Top Gear. Available at: https://www.topgear.com/car-news/formula-one/what-porpoising-f1s-aerodynamic-phenomenon-explained